Cloth, when sewn together, becomes clothing. Just how valuable was clothing in former times? The answer far surpasses anything we imagine in the modern day, when we can buy mass-produced, imported clothing for the slightest sum. For us, clothes are nothing more than a consumable good. In the past, however, ordinary citizens could count the number of outfits they owned over their entire lifetime. It’s incredible to think that rolls of white cloth were once formally presented to feudal lords as gifts.

To make their precious clothing last longer, people would take needle and thread and embroider them with reinforcing stitches. This style of functional embroidery is called sashiko (literally “little stabs”) in Japanese. Sashiko was widely used in Japan and other parts of the world, as it made cloth thicker and added insulation from cold winds.

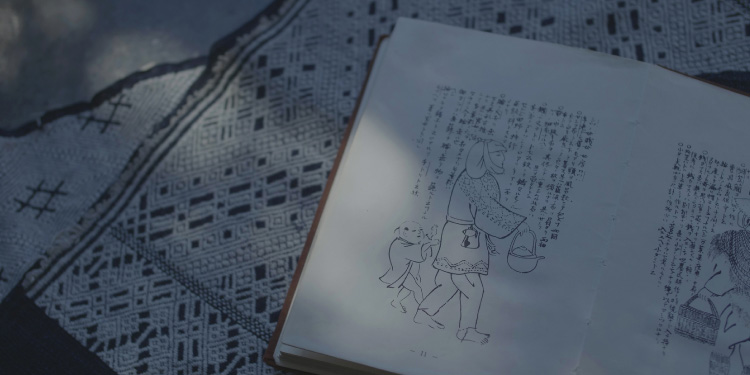

The Tsugaru region of northwestern Japan around what is present-day Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, gave birth to many distinctively beautiful sashiko patterns. Farmers in Tsugaru called their work clothes koginu, and these included a short coat made of hemp cloth that was dyed indigo blue. The shoulder and front and back chest portions of the coat would be covered in sashiko embroidery, giving rise to its name of koginzashi.

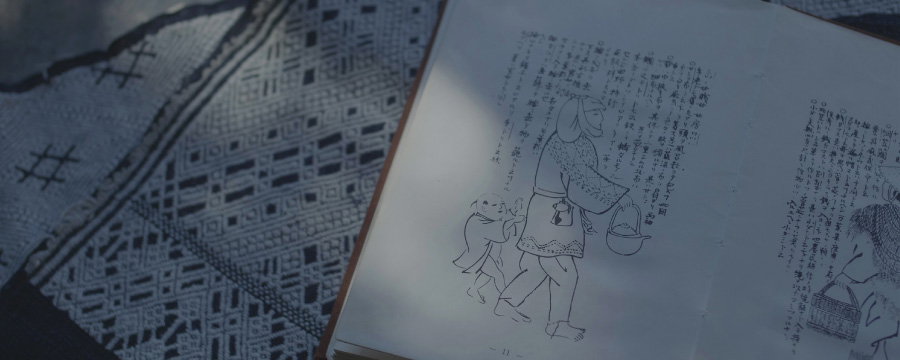

Koginzashi patterns are recorded in the Omin-zui, a collection of prints depicting life in Tsugaru that was published in 1788. Based on this, it can be surmised that the patterns developed organically some time before this.

Daughters in farming families would begin practicing their embroidery stitches at a young age and embroidered clothing for their family and for their future husband. The finest embroidered pieces were worn on special occasions. The intricate patterns were developed over generations of women lending their creativity and skill to the practical art. Their names are not remembered by history, but the stitches bear witness to their lives.

There is no unsightly kogin—not one. You cannot find any even if you try. There may be some differences in quality. Some patterns may be slightly better or worse than others. But none are bad. Why are there no unsightly kogin? It’s no secret. The answer lies in kogin’s orderly following of rules.

(Kogin no seishitsu [The nature of kogin], Yanagi Muneyoshi)

The rules Yanagi refers to come from the regular order of the horizontal weft and vertical warp threads. Kogin stitching is a counted thread embroidery. The patterns naturally arise from stitches over and under odd numbers of warp threads and the shifting number of warps in each row. This creates geometric kogin patterns that are beautiful regardless of the hand that stitches them.

Koginzashi flourished from the Edo Period (1603–1868) to the middle Meiji Period (1868–1912). The opening of rail lines brought warm, fashionable kimono from other areas, and the art of sashiko quickly declined. Yanagi Muneyoshi wrote the above passage in the early Showa Period (1926–1989). By that time, almost no one practiced the functional art anymore. Sashiko was originally not sold in markets as a product, but was a domestic art of the common people created from necessity and love.

Nonetheless, fine examples of this heritage still exist today, and some people are carrying on the tradition of sashiko. As long as the stitches follow their numerically imposed order, the patterns maintain the same beauty. Kogin remains alive today with cloth, needle, thread, and the patient hands that make each stitch. The modern women of Tsugaru create kogin in their time spent stitching—and from the heritage of the exquisite patterns left to us by anonymous women of long ago. The humble clothes continue to give back, even in the modern day.

職種:店舗販売 / 営業 / 生産管理 / パタンナー / デザイナー

正社員登用、給与は経験により相談。月20万円以上。

年齢性別不問。

厚生年金、健康保険、雇用保険等完備。交通費支給、賞与。

ご希望の方は、メールにて履歴書と職務経歴書をお送り下さい。

通過者のみ面接の返信をいたします。なお募集の職種は時期によって異なる場合があるのでお問い合わせください。

*学生のインターンは随時可能ですので、希望者は面接いたします。

送信先メールアドレス:matohu@lewsten.com

◇ matohuの理念

「日本の美意識が通底する新しい服の創造」をコンセプトに文化や歴史を大切にしながら、現代人の心に響く魅力ある「デザイン」を生み出すこと。それを深い「言葉」で表現し、共感者の輪を拡げて行く「場」を作って行くこと。

この3つを通して、多様で心豊かな世界をともに作り上げることがmatohuのプロジェクトであり、理念です。

◇ 仕事のやりがいと人間的成長

まかされた仕事を自分の創意で工夫していける環境です。1Fはショップ、2Fはアトリエになっており、デザイナーと直接話しながらアイデアを実現していけます。また文化、歴史など幅広い知識を学ぶ機会も多く大人の教養と礼儀が身につき、人間的にも成長できます。

人の心に彩りを添えるデザインを生活のなかに!を合い言葉にこれから世界に向けて発信するmatohuのスタッフを募集します。